Restoring the Skutik

(Excerpt Saltscapes Magazine, Oct/Nov 2024)

Thanks to Indigenous leadership and an international collaboration, the alewives run again

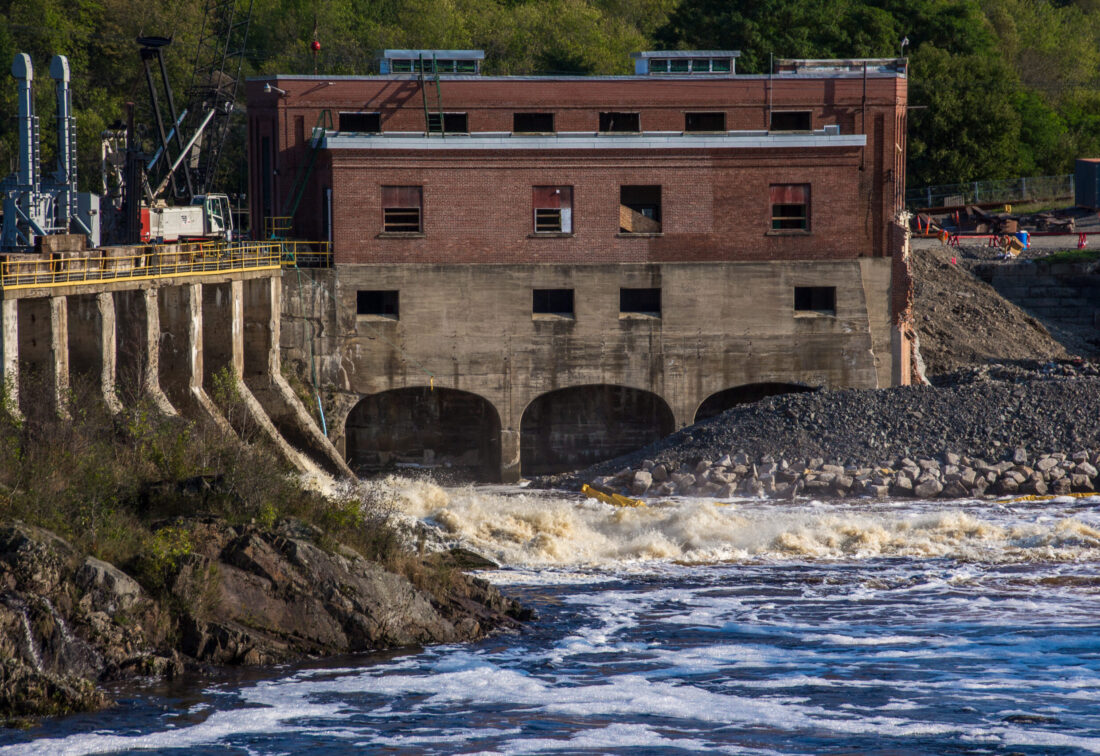

On a late September day in 2023, I meet Chief Hugh Akagi of the Peskotomuhkati Nation at Skutik and Fundy Baykeeper, Matthew Abbott, at a small memorial park on the banks of the Skutik (St. Croix) River overlooking the Milltown Power Generating Station.

Far below, a channel of water on the opposite shore thunders past the station housing one of the oldest hydro dams in Canada and rushes over a rock outcropping, cascading in a creamy froth to the river below. The rest of the river’s width remains hidden behind sections that NB Power began decommissioning in July. In another month, the station would also be gone.

Abbott breaks the silence. “A decade ago,” he says, “we could not have dreamed of this.”