A Tale of Two Women

(Saltscapes Magazine, Jul/Aug 2015)

New Brunswick has been well served by two dynamic women who worked tirelessly for environmental justice.

In 1962, Rachel Carson’s seminal book, Silent Spring, which explored the links between pesticide use, wildlife mortality, and human cancer, sparked what became a global environmental movement. Educated as a marine biologist, Carson was a reluctant activist compelled by her sense of justice. She wrote to a friend, “Knowing what I do, there would be no future peace for me if I kept silent.” Carson died of cancer just two years following the book’s publication. Although subjected to vicious attacks by the chemical industry and policy makers before her death, her conviction and work changed history and inspired generations of environmental voices.

New Brunswick’s Dr. Mary Majka and Inka Milewski are two of those voices.

Mary

On June 14, 2014, a crowd gathered in a rural hall not far from Mary’s Point, NB to celebrate the life and legacy of naturalist, Dr. Mary Majka, who had passed away the previous February at the age of 90.

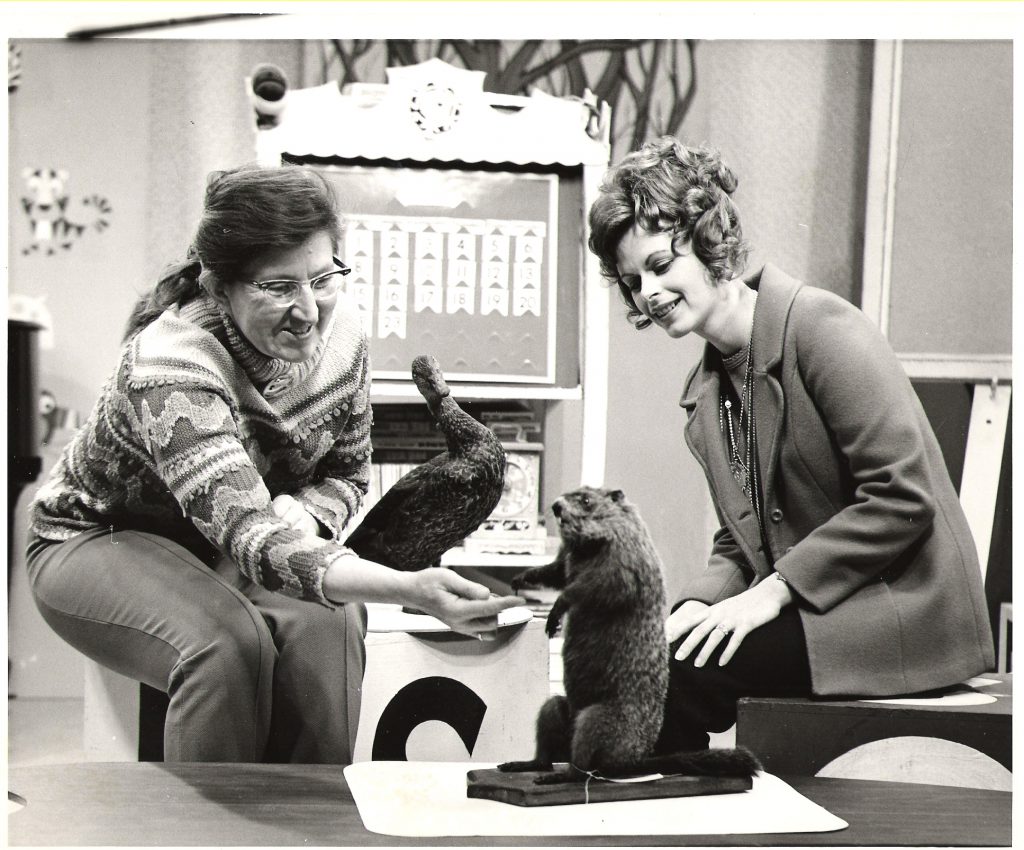

Mary was a pioneer in the fledgling environmental movement in New Brunswick. Although widely-recognized for her 1967-74 children’s television show, ‘Have you Seen?’, and for her life’s work protecting fragile habitats like the Mary’s Point Shorebird Reserve, Mary also contributed to the first environmental organizations, advocated for better environmental legislation, and undertook projects to safeguard the cultural and natural heritage of her adopted country.

Mary was a pioneer in the fledgling environmental movement in New Brunswick. Although widely-recognized for her 1967-74 children’s television show, ‘Have you Seen?’, and for her life’s work protecting fragile habitats like the Mary’s Point Shorebird Reserve, Mary also contributed to the first environmental organizations, advocated for better environmental legislation, and undertook projects to safeguard the cultural and natural heritage of her adopted country.

Her accomplishments are as lengthy as the awards she received (including the Order of Canada and the Order of New Brunswick), but on this day, what lingered in the minds of those present, were the ways that her enthusiasm for life had inspired others to action. She was an authentic and impassioned voice for nature.

Inka

On her farm near the outflow of the Miramichi River, 60-year-old marine biologist Inka Milewski watches for bobolinks and barn swallows above the emerald fields and tidy rows of raspberry bushes. Her own watercolours of birches hang on the walls of the bright and airy home. Their spare, lean lines, striking in black and white and shades of grey, seem apropos of the slender woman seated at the table.

On her farm near the outflow of the Miramichi River, 60-year-old marine biologist Inka Milewski watches for bobolinks and barn swallows above the emerald fields and tidy rows of raspberry bushes. Her own watercolours of birches hang on the walls of the bright and airy home. Their spare, lean lines, striking in black and white and shades of grey, seem apropos of the slender woman seated at the table.

She places her hand upon the stack of reports on coastal habitat destruction and cancer rates in New Brunswick communities that represent much of her recent labours as Science Advisor with the Conservation Council of New Brunswick. “These are more than reports for me,” says Inka. “These are hope. These represent work at a community level after citizens came forward to say there is something wrong. This is citizen science.”

She is determined to be a voice for those citizens. And for justice.

Being ‘Other’

As the daughter of an affluent Polish high school principal and an Austrian countess, Mary possessed both her father’s respect for nature and heritage, and her mother’s altruism. Nannies, custom clothes, spa vacations, and summers by the Baltic sea were the norm, but when Mary was 12, her father committed suicide, plunging the family in financial ruin. During this time, Mary sought solace in nature.

Four years later, Hitler invaded Poland. While her mother and brother fled safely to Austria, Mary spent the war years incarcerated in concentration and work camps, then later as a captive farm labourer in the mountains of Austria. She met her husband Mieczyslaw in a Displaced Person (DP) camp after the war and they immigrated to Canada, landing at Halifax’s Pier 21 in 1951.

Like so many others, they carried the invisible scars of war, but also hope and optimism, and a love of wide-open spaces. They travelled by train to the industrial landscape of Hamilton, Ontario, where Mary found work as domestic help, learning English from radio and Reader’s Digest.

She quickly discovered that while DP was a label worthy of pride in post-war Europe, it invited scorn and insults in immigrant-weary Canada. “You had to be strong not to get discouraged,” she said. “But in a way, that produced a great resolve to show that I was as good, if not better. Perhaps this is what drove me…I had been shunned and treated as a second-class citizen, but I determined I would not feel like one.”

Inka Milewski’s parents had arrived the previous year as indentured labour. While Hania worked in a school for the deaf, Tadeusz found employment in an Ontario gold mine, then later in the uranium mines at Elliot Lake. Billed as the Uranium Capital of the World, Elliot Lake had 11 operating mines when the Milewski’s moved there.

Growing up, Inka also felt the sting of being an ‘Other’. She met the taunts of children who could not pronounce her name, or called her Dumb Polack, with defiance. “I thought of myself as the same as everyone else, so didn’t understand why they would call us names. I didn’t have the language to put to it, but I felt it unfair and unjust. I had a sense it was wrong.”

Her parents advised her to remain silent; to be invisible. “I didn’t like that kind of advice. If something was wrong, I would say so. It was in my nature to challenge authority and arbitrary decisions. And if I was pushed, I would push back.”