Restoring the Skutik

(Excerpt Saltscapes Magazine, Oct/Nov 2024)

Thanks to Indigenous leadership and an international collaboration, the alewives run again

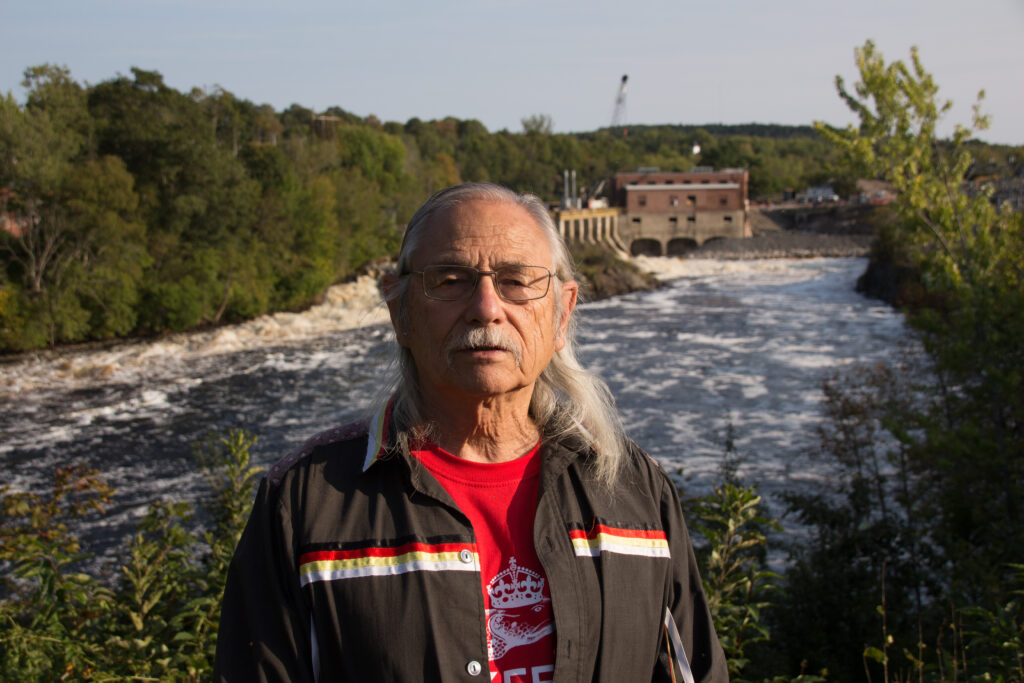

On a late September day in 2023, I meet Chief Hugh Akagi of the Peskotomuhkati Nation at Skutik and Fundy Baykeeper, Matthew Abbott, at a small memorial park on the banks of the Skutik (St. Croix) River overlooking the Milltown Power Generating Station.

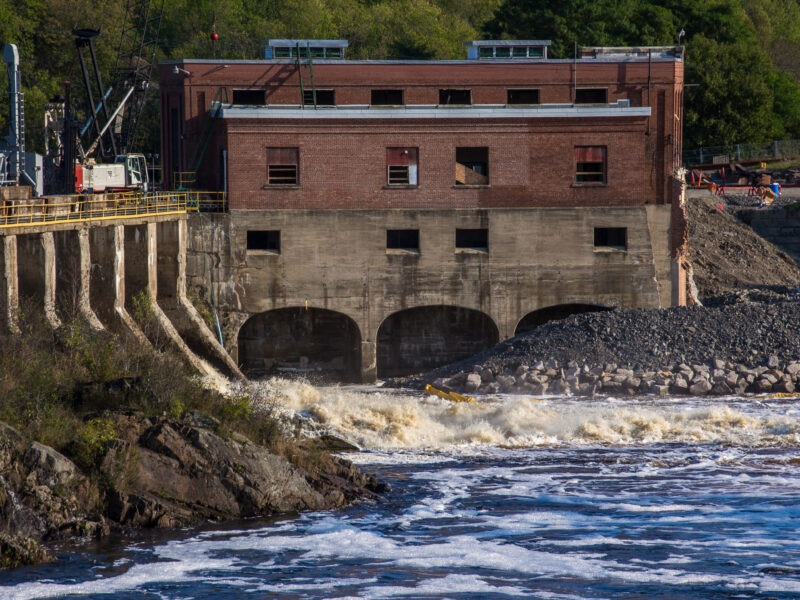

Far below, a channel of water on the opposite shore thunders past the station housing one of the oldest hydro dams in Canada and rushes over a rock outcropping, cascading in a creamy froth to the river below. The rest of the river’s width remains hidden behind sections that NB Power began decommissioning in July. In another month, the station would also be gone.

Abbott breaks the silence. “A decade ago,” he says, “we could not have dreamed of this.”

Chief Hugh Akagi of the Peskotomuhkati Nation at Skutik and Fundy Baykeeper, Matthew Abbott

Back then, Abbott was participating in a 130-kilometre relay run from Sipayik (Point Pleasant, Maine) to Forest City, N.B., a route that follows the spawning migration of the Siqonomeq (known as alewife, river herring, or gaspereau), a small fish indigenous to the river system. At that time, 98 per cent of its prime spawning habitat was inaccessible to the alewife due to multiple dams and obstructions. The population, having plummeted to 16,000 fish from over 2.6 million in 1987, was in crisis.

The relay was an act of awareness and a cry of protest.

“There’s a long tradition of sacred runs with the Wabanaki,” says Abbott, referring to the alliance of First Nations of the northeast: the Abenaki, Penobscot, Passamaquoddy, Mi’kmaq, and Wolastoqey.

In May 2023, they held another relay. This time, the mood had shifted. The alewife no longer had to navigate the Milltown fishway. The first of many artificial barriers on their northbound migration from ocean to river spawning grounds was gone.

“It was super emotional,” says Abbott. “I was running with some of my heroes. You know things are going well when something starts as a protest and ends as a celebration.”

Chief Akagi points to the channel where water surges past the generating station. “We call this the Salmon Falls. That’s where the fish ladder was. It allowed salmon and other fish passage up the falls and past the dam.”

The soft-spoken chief said ladder removal was the first stage in decommissioning the dam and restoring approximately 16 kilometres of river, five million square metres of spawning habitat, in the Skutik. When complete, the full width will be open again.

“We are specific to our river,” Akagi says. “This river is what defines me.” He watches the current froth over rock. “People forget what we really had here.”

The People

Before retiring from the Sipayik Environmental Department in Maine, Ed Bassett was one of the earliest voices advocating for river restoration.

“What happened to the river and the fish is a metaphor,” says Bassett. “A living metaphor for what has happened to the Passamaquoddy. By law, the fish have been blocked or banned from spawning in their native habitat to almost the point of extinction, and for native people, that’s also a pretty common story.”

The traditional home of the Passamaquoddy (called Peskotomuhkati on the Canadian side) once encompassed 16,257 square kilometres between the watersheds of the Penobscot River in Maine, and the Wolastoq (Saint John) River in New Brunswick. The Skutik watershed was the beating heart of this territory, providing the tribe with physical, cultural, and spiritual sustenance.

The traditional home of the Passamaquoddy (called Peskotomuhkati on the Canadian side) once encompassed 16,257 square kilometres between the watersheds of the Penobscot River in Maine, and the Wolastoq (Saint John) River in New Brunswick. The Skutik watershed was the beating heart of this territory, providing the tribe with physical, cultural, and spiritual sustenance.

“Our homeland,” wrote Bassett in a report documenting his nation’s relationship to the river and the alewife, “offered the Passamaquoddy a rich and diverse environment … pristine woodlands, fertile valleys, mountains, island, fresh water lakes, rivers, salt water estuaries, and the ocean with incredible tides offering limitless supplies of food twice a day.”

The Passamaquoddy, which means People of the Pollock (a marine species once plentiful in the region), enjoyed a deep connection with both inland and marine environments. They easily traveled the waters of the river and bay in birch bark canoes. An ancient fishing village known as Siquoniw Utenehsis existed at the Salmon Falls. The people converged there each spring to harvest the sea-run fish.

When the pollock ran close to shore, Bassett wrote, “Many community members would come down to the beach and wade into the water and simply grab the large Pollock by the hand or with a pitchfork and then fill everyone’s baskets.”

They also fashioned fishing nets and weirs to capture the migrations of alewife and salmon. The diverse harvest provided fresh food, while smoking preserved nutrition for the winter months.

“This region was known as a nursery ground for whales and porpoises, its own unique ecosystem that you wouldn’t find anywhere else in the world,” Bassett says. “A Fundy oasis; an oasis in decline. No wonder the Passamaquoddy wanted to live here. It was a garden of Eden.”

His people lived in companionship with the river for more than 13,000 years.

Then, in 1604, Samuel de Champlain and his crew sailed into the mouth of the river. They spent only one ill-fated winter on a small island, but it signified change. Europeans had arrived. Soon, buildings and roads were built atop ancestral homes and burial grounds. The settlers began exploiting the natural resources, constructing a cotton mill and tannery, industrial sawmills, pulp mills, and dams along the river. In 1798, United States and Canada delineated themselves, settling on the river as a boundary. By then, the Passamaquoddy had also been split up and displaced; most on reservations in Maine, and others spread throughout their territory in New Brunswick. The river that bound them, now separated them.

The People of the Pollock suffered, and the Skutik suffered. The alewife began to disappear, and all that depended upon it.

“That balance had been there for thousands of years,” says Bassett. “And in a matter of 300 to 400 years, it was totally destroyed.”

(Read the rest Saltscapes Magazine, Oct/Nov 2024 issue)